Anatomy of Time

Public Art Commission Bond St, Elizabeth Line

London, January 2024

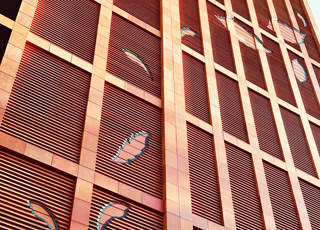

Artist Clare Twomey has created a new public artwork that transforms the Bond Street West Elizabeth Line station. The sculptural façade seems to emerge from the ground and climb the southwestern corner of Grosvenor’s new 65 Davies Street development. The artwork, Anatomy of Time, commissioned by Grosvenor, is based on the local ancient plants and water ways is a vast yet gentle composition of the local botanical narratives indented into the façade of the building creating an artwork that is embedded into the building and flows out of its terracotta façade. The placement of the leaves that cut through the building piers flow and lead our gaze towards the sky and the surrounding trees. Tracing the path of the River Tyburn, and carved into the surface of the building, the leaf shapes sustain a relationship with the architecture and local area. The leaf patterns were inspired by William Curtis’s Flora Londinensis, a pioneering study of urban nature that recorded 430 flowering species within a 10-mile radius of London.

“To some extent, this work was an extension of past works and of my environmental concerns and the understanding that if we nurture nature, we might not lose it. I hope it will help people to see that if we work hard, we can still find nature, even in central London. Maybe they’ll walk past it, or maybe they’ll have a favourite leaf, or read up on all the leaves, and look at their neighbourhood differently.”– Clare Twomey, interviewed by Alice Rawsthorne

+ Further reading

Clare Twomey, Anatomy of Time

On the west face of 65 Davies Street, Clare Twomey’s Anatomy of Time rises six storeys above street level on a magnificent canvas of terracotta louvres. This landmark artwork is the largest of its kind in Mayfair, opening an exciting new chapter for public art in the area — and marking a significant new milestone for women artists.

Despite its soaring prominence, Anatomy of Time is firmly rooted in its immediate locale. It draws inspiration from the site’s natural and physical history, while holding a synergetic dialogue with the materials and motifs of its surroundings. The work also reaches forwards, maintaining a deeply respectful eye on its legacy to neighbours and neighbourhood.

Ten leaves, carved from the clay in counter-relief, cascade across the building, as if carried away on a fast-running brook — specifically, in fact, the Tyburn, one of London’s ancient rivers which still courses through culverts directly beneath the building.

In changing light, subtle differences in the shades of the terracotta and the varied coloured glazes at the margins of the leaves animate the façade, particularly beneath the dancing shadows cast by the trees opposite. The sense of lightness and movement, evoked further by the carved-out negatives of counter-relief, captures the ephemerality of urban flora and the transient footfall on the streets below.

Significantly, they are leaves and not flowers. These are the working engines of the plant, rather than the parts normally used for ornament. Neither are they generic or gardeners’ favourites, but leaves from everyday city plants — ivy, periwinkle, soapwort, wild clary and gypsy rose — chosen definitively because they once grew here and would have been familiar to Londoners working and living here.

We can be sure of this thanks to the great botanist William Curtis (1746—1799), who made it his life’s work to document every plant growing in London in his masterpiece, Flora Londinensis, one of Clare’s principal inspirations. Enlisting the most gifted natural artists of the age at enormous personal expense, Curtis almost ruined himself in the work’s making, but by 1798, the year before his death, he had succeeded in describing more than 430 London plants in hitherto unmatched detail. Curtis’s mission in Flora Londinensis was to communicate the value of ordinary native plants, for medicine, agriculture and manufacture. Even as young boy, he had bewildered his father by deliberately cultivating ‘weeds’ — which he did, observing that certain insects and butterflies favoured them above others. When training as an apothecary (at the insistence of his father, who was trying to wean him away from botany), he infuriated his superiors by paying an artist three guineas, a small fortune, to make an engraving of a common nettle.

His conviction that even the lowliest city plant should be championed is arguably more important now than it was in Curtis’s day. Urban nature is under extraordinary and mounting pressures, squeezed ever closer to its tolerable limits.

But city flora can also show remarkable resilience – and the plants of Anatomy of Time could still flourish in Mayfair as they once did beside the Tyburn.

Accompanying this text are the seeds of these five London plants. You can grow to create: from soapwort, you can make cleansers; from gypsy rose, skin cream; the stems of periwinkle are perfect for cord and twine; while the leaves of wild clary are good to eat; animals and birds love nesting in ivy, which can also insulate exposed walls. Or you could grow them simply to enjoy, as Clare suggests, as your own artworks.

William Curtis supported anything that celebrated the natural world and brought communities closer to it. Anatomy of Time invites us to reflect on the past and consider the future, while we stand here, in the heart of London, on the fulcrum of the present.

Harry Adès, Author, The Botanical City, London 2023

anatomy of time by clare twomey was commissioned by grosvenor through selective competitive invitation. 65 davies street, an innovative new workspace development from grosvenor, was designed by plp architecture.

Q & A | Clare Twomey with Alice Rawsthorn | Anatomy of Time

AR: How did the project come about?

CT: It’s an interesting question, because it is unusual for me to undertake a permanent work. I was one of four artists who were invited by Futurecity to look at the brief to make a public artwork for a new office building in Mayfair, designed by PLP Architects for Grosvenor Estates and built on a ventilation shaft of the Elizabeth Line. I felt it was a brilliant opportunity to make something beautiful for passers-by, local residents and workers to enjoy. Also my sense of the two female artists a generation or two before me, Barbara Hepworth and Wendy Ramshaw, making work close to this site was really important. They both made work bigger than themselves. Their strength tells us why women are so needed in monumental sculpture.

AR: And how did you develop the concept?

CT: The process was extremely open, which gave me a broad framework to decide what I felt would be important. My starting point for this project was to think how the artwork would be viewed in a hundred years. Then I decided to also look backwards at the history of the Grosvenor Estates and how time has treated the area and its landscape. Three things emerged. One was to embed the work in PLP’s terracotta façade. The second was that it should refer to Mayfair’s natural history and to the plants and trees that once thrived there. The third was that the new building stands directly above a stretch of the River Tyburn; one of the “secret rivers” that once flowed through the central London and are now culverted, or enclosed, by pipes.

AR: All intriguing references. Let’s start with the terracotta. Why did you choose to use it?

CT: At the beginning of the project, there were lots of questions about which material we would use, and who we would make the artwork with. The thing I kept coming back to was that I wanted the artwork to be part of the new building from the ground upwards, rather than being added on to it. Ron Bakker of PLP had already designed a beautiful terracotta façade and terracotta is at the heart of Mayfair’s architectural history, having been used to clad and decorate so many buildings in the area. It made sense for my artwork to be aligned with the façade and to be made by NBK Architectural Terracotta, the German manufacturer, that the architect Ron Bakker was working with.

AR: And how did you choose to represent Mayfair’s natural history?

CT: I did lots of research and, as usual, once you start working on something, new ideas cross your radar. I came across a book by someone I had never heard of, the 18th century botanist William Curtis, who published brilliant surveys of urban nature in The Botanical Magazine and a book, Flora Londinensis, on wildflowers growing in the London area during the mid-18th century. While I was undertaking the research, a new book was published entitled, The Botanical City, featuring the plants identified by Curtis. I selected five plants from it that would have been likely to have grown near a river like the Tyburn at the time, and to depict their leaves on the terracotta façade. The leaves are also a reference to the lovely ivy leaves carved out of a brick in a nearby wall of the Peabody Building. When I saw them I thought that they seemed like hovering narratives in the local area which helped to convince me that the local was really important to the artwork. There is an ivy leaf among the ones I chose to represent on the façade. The others are Gypsy Rose, Periwinkle, Soapwort and Wild Clary .

AR: How is the river represented? And when did you become aware of London’s ‘secret rivers’?

CT: I started life in London living in Brixton as a student, and became aware of the underground rivers there. Discovering that the River Tyburn ran directly beneath the building sparked my imagination to find out more about it and other ‘lost’ rivers. There is a nearby antiques shop, just off Davies Street, where it is said that a culverted section of the Tyburn runs through the basement. The Tyburn was never a powerful river. It probably wasn’t much more than a stream. But it ran from South Hampstead through Marylebone and Mayfair into the Thames and is part of the sites history. So I positioned the leaves to travel across the façade in the same direction as the Tyburn, as it runs from Gilbert Street to Westminster, and into the Thames.

AR: It’s a lovely nod to local history, and to London’s secrets. And the leaves seem to sit effortlessly on the terracotta louvres cladding the building. How difficult was it to achieve this affect, especially as each louvre is cast at a specific angle?

CT: Very difficult! Everybody has used extraordinary skills in enabling this work to be made, but it was complex. NBK Architectural Terracotta have previously undertaken some incredible technical projects, but nothing exactly like this. They don’t carve clay, which made it very difficult for them to curve the angles correctly and to ensure that the glaze creates the correct light effects at different times, and in different weather conditions. I have carved clay and was helped by the team from the structural engineers, Arup, who helped enable my ideas with the factory. Even so, it was challenging. Then the factory found Mathias Deutz, an employee whose hobby was making cornices. He was hugely knowledgable. He had all the skills and fluidity in his hands, and he understood the nuance between creating a very sharp line or a curved line.

AR: How amazing that Mathias’s cornicing skills proved so important in realising the artwork. Am I correct in thinking that working on this project must have felt slightly unusual for you? Most of your past projects have been collective to some degree, often including community involvement, such as the Factory ceramics workshops at Tate Modern in 2017 and 2018 and Manifest: 10,000 Hours, an installation exhibited at York Art Gallery from 2015 to 2017 for which 10,000 bowls were made by hundreds of ceramicists throughout the UK. For those projects, you set a framework, and empowered other people to interpret it. But for Anatomy of Time you set a framework and then negotiated with the makers to realise your vision. In other words, it was a more conventional way of developing a public artwork whereby the artist designs it in consultation with the architects and then entrusts its fabrication to skilled workers.

CT: It was a new process for me. Working with architects is something I don’t usually do. We had lots of conversations about the shapes of the leaves, whether to show the inside or outside, and how to allow for distortions created by changes in the light. The shadows of the leaves are also very different in the morning than at night, and the shadows of nearby trees fall differently on the façade at different times of the year, which creates complexity, as do the terracotta louvres. The way the architects interpreted all of this was brilliant. There are a lot of new processes in the work, but it is so well made, and the quality of the craftsmanship is unbelievable. At some points, the leaves look like sculpture, and at others like strange little slithers of glaze. It’s only when you stand back from the building that you see the whole and think: ‘Oh. That’s how it works’.

AR: Was it also a new process for you from a formal perspective? Are there links to your previous projects, or is it an outlier?

CT: That’s a lovely question because, in a way, Anatomy of Time wasn’t a stranger because of the other botanical works I’ve made, for example, Specimen, for an exhibition at the Royal Academy and Blossom for the Eden Project in Cornwall. To some extent, this work was an extension of them and of my environmental concerns, and the understanding that if we nurture nature, we might not lose it. I hope it will help people to see that if we work hard, we can still find nature, even in central London.

I also hope that the local residents and workers will see this work as being theirs. Maybe they will walk past it, or maybe they will have a favourite leaf, or read up on all the leaves, and look at their neighbourhood differently. I realised through the production period that I wanted to make packets of seeds of the plants, whose leaves are part of the work, so that the local residents and their neighbours can cultivate the plants in window boxes or gardens. It is a way of inviting them into the artwork.

+ View Video